[Editor's Note: When we shared our Happy Birthday Ritchie Valens story on Facebook last Friday, FB user Danna Carina commented, "Ritchie was the subject of my senior thesis and I graduated with my Bachelors yesterday ON HIS BIRTHDAY. Good omen I suppose!"

[Editor's Note: When we shared our Happy Birthday Ritchie Valens story on Facebook last Friday, FB user Danna Carina commented, "Ritchie was the subject of my senior thesis and I graduated with my Bachelors yesterday ON HIS BIRTHDAY. Good omen I suppose!"

We wanted to see what she wrote, and to share it with you.

She agreed, and noted, "Writing this paper was a very intimate and intellectual experience, so it makes me very happy to share it with Pocho.com and the Chicano community."

Thank you, Danna Carina, and congratulations on your graduation from SUNY Purchase.]

Danna Cruz

Senior Capstone

Professor Konzelman

March 4, 2016

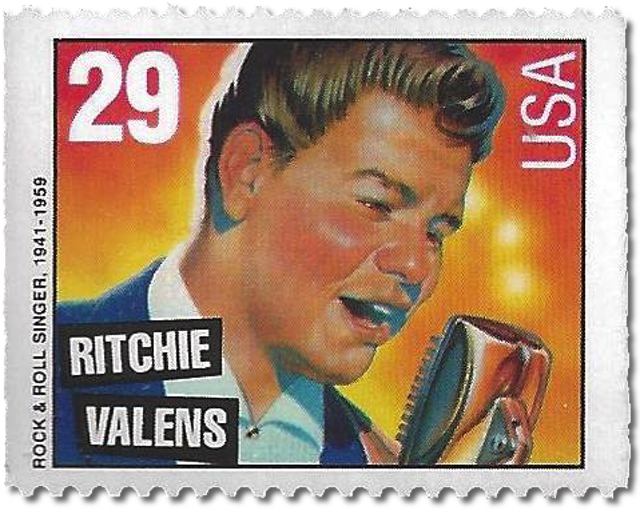

PASSION AND SIX STRINGS: RITCHIE VALENS AND

THE CREATION OF CHICANO ROCK IN THE U.S.A.

“Looking to the world at no very distant date, what an endless number of the lower races will have been eliminated by the higher civilized races throughout the world.”

– Charles Darwin, “Life and Letters to W. Graham 1881”

“The days of the pure whites, the victors of today, are as numbered as were the days of their predecessors. Having fulfilled their destiny of mechanizing the world, they themselves have set, without knowing it, the basis for the new period: The period of the fusion and the mixing of all peoples.”

–Jose Vasconcelos, “La Raza Cosmica 1925”

The evolution of humankind is unpredictable by nature, but two things are certain; although we are bound to die, we are not nil, and while we are still alive, changes will persist. Darwin’s and Vasconcelos’ philosophies on the evolution of civilization elucidate the advent of Richie Steven Valenzuela, known as Ritchie Valens. Migration has ushered some of the greatest thinkers, artists, and musicians onto the global platform to be lauded by listeners. Migration also led to the development of a unique group of Americans who began to call themselves “Chicanos”. The Chicanos’ parents had been born in Mexico. The Chicanos themselves were born in the United States to Mexican parents. Ritchie Valens’ passion, Chicano Rock n Roll, unfolded before the American popular audience in the 1950s, as a result of migration. The musical gift of Valens not only brought jubilation to his audiences during his time alive, but also after he died. Most importantly, this young musician caused an increase in self-esteem and expressive opportunities for the Chicano community.

The evolution of humankind is unpredictable by nature, but two things are certain; although we are bound to die, we are not nil, and while we are still alive, changes will persist. Darwin’s and Vasconcelos’ philosophies on the evolution of civilization elucidate the advent of Richie Steven Valenzuela, known as Ritchie Valens. Migration has ushered some of the greatest thinkers, artists, and musicians onto the global platform to be lauded by listeners. Migration also led to the development of a unique group of Americans who began to call themselves “Chicanos”. The Chicanos’ parents had been born in Mexico. The Chicanos themselves were born in the United States to Mexican parents. Ritchie Valens’ passion, Chicano Rock n Roll, unfolded before the American popular audience in the 1950s, as a result of migration. The musical gift of Valens not only brought jubilation to his audiences during his time alive, but also after he died. Most importantly, this young musician caused an increase in self-esteem and expressive opportunities for the Chicano community.

Ritchie Valens is the epitome of the quote, “only the good die young”, for he perished in a plane crash at the age 17. I have studied the foundations of his life, his successes, and his role in the creation of Chicano Rock n Roll in the U.S.A. Along this journey, I had the pleasure of recalling my personal and first-hand experiences as a Chicana, for they are relevant and were, in some way, shaped by this rock star. I am a descendent of indigenous Mexican migrant working people, raised in Southern California. With my father’s help, I developed an ear for world music. Most intriguingly, my name was influenced by Ritchie’s sweetheart, Donna Ludwig. In my research, I have also had the opportunity to identify and mention two of the universal things that we share as species; passion and music.

Charles Darwin’s evolutionary prediction that an attempt would be made by hegemonic cultures to eliminate minorities would prove true during the twentieth century. Jose Vasconcelos predicted the arrival of a diverse, multicultural society. This was a previously unimaginable state of affairs. The mixing of cultures has certainly shaped livelihoods and generations of people, in ways that cannot be undone.

The 1987 biographical film on Ritchie Valens, “La Bamba”, created by Luis Valdez, was my first exposure to Chicano rock star Ritchie Valens. Interestingly, Ritchie’s family members had small roles in the film. I remember the day I watched it, as if it happened last night. It is one of my most delightful memories. I was a nine year old living in Southern California alongside other migrant working families. It was the weekend, and everyone working the fields in the Santa Maria Valley had the day off, so this meant relaxation day with the family. The morning was sunny and energized, but by evening time, my family gathered in the crowded living room to watch a film. A video cassette of the film “La Bamba” was inserted into the VCR. The lights disappeared in the room, leaving only the vibrant shots of the film as the object of my vision. The adults in my family were not fluent in English, but that did not stop them from watching. The soundtrack of the film made this movie experience worthwhile for everyone. One second it was Chicano Rock group Los Lobos singing out from the television screen, and the next it was Italian duo Santo and Johnny’s serene “Sleepwalk”. There were surreal moments, especially when Ritchie Valens’ character, played by Filipino-American actor Lou Diamond Phillips, began to sing “oh, Donna, oh Donna, oh Donna, oh Donna.” That was when I really knew this moment was special. Everyone in the room turned towards me and began to sing “oh, Donna, oh Donna” with a good-natured smile. It took a few seconds before a “ding!” went off in my head, my ears perked up, and I uncovered the origin of my name. I will admit, I felt exceptional in that moment. The next couple of days I went on synchronizing my foot to the melodies of his songs. My imagination, too, toyed with the idea of being a rock star. Similarly today, I take a fancy to 1950s history, music, apparel and speech. So, in a comical sense, Ritchie Valens has shaped my character, my interests, and my destiny.

If it were not for films like “La Bamba”, or photographs, radios, cassette tapes, compact discs, and television shows, people would not know about Ritchie Valens and his music. As such, he became known beyond the borders of his neighborhood of Pacoima, California. In fact, from his birth on May 13, 1941 up to his death on February 3, 1958, the United States experienced an exponential boom in consumerism. The increased resources allowed unique artists like Ritchie to become popular on a national scale. However, while the wealthy and middle class families could afford decent shelter and new belongings, such as record players and records in their homes, the “immigrant” Mexican population of Los Angeles, who were less financially stable, were not so fortunate. These working families were instead struggling to make ends meet. They lived in broken-down neighborhoods, and worked endless hours of intense labor in factories and in fields, with little pay. This was the case for many Mexican families in the states. The Chicanos, as the younger and American-born Mexicans, had an advantage when it came to education and working outside of the fields, but it was a very slight advantage. Nevertheless, it was more than what incoming migrant Mexican working families were exposed to.

Ritchie’s parents, Concepcion “Connie” Valenzuela and Joseph Steven Valenzuela, his sisters Connie and Irma, as well as his brothers Bob and Mario all made their home in the Pacoima Neighborhood in the San Fernando Valley (in Los Angeles) in the late 1940s. Although it was referred to as a “suburban” area, the majority of the population at the time were second or third generation Mexicans, or Chicanos. His father, Joseph Steven Valenzuela took on an array of jobs such as pruning and treating old or damaged trees. At other times he worked as a miner, excavating minerals that benefited others, or spent his day training horses for the more fortunate. As for his mother, Concepcion, she took on a job working in an ammunition-making plant. Having two working parents in jobs with conditions that were less harsh than fieldwork later gave Ritchie the opportunity to grow up in a slightly better environment.

Just like Concepcion and Joseph, my parents, too, sacrificed their time and hard work to give my five siblings and myself opportunities to grow out of poverty. They took on any jobs from picking blueberries in Virginia and planting green beans in California, to working factory jobs that manufactured stuffed animals or fabric in North Carolina. While they worked we attended school. When times were not so good, we all worked in the fields picking and packing strawberries. The smell of the wet soil and pesticide lingers underneath my nostrils in moments of nostalgia like this one. The generous dawn would accompany workers up until sunset while backs were bent and layered with “protective” clothing. Our parents were not proud of having us there working, but they knew working would be something we would have to learn one way or another.

Joseph and Concepcion’s decision to settle in the suburban Pacoima neighborhood meant they sought opportunity for their children; opportunity, that is, to attend public school, master English, and make both Chicano and non-Chicano acquaintances. Joseph and Concepcion “called it quits” by the time Ritchie turned three. The couple had their personal reasons for separating, but this did not stop them from sharing custody of the children. His parents’ separation also did not stop the environment from impacting what would later be Ritchie’s teenage life.

What was taking place nationally was a different scenario. By the time Ritchie was four years and four months old, in 1945, the horrendous Second World War had just concluded. The results of World War II appeared to confirm the prognosis made by Charles Darwin; the “lower races” of Europe would be victims of genocide by a “higher race.” The higher race in this case, was Nazi Germany. Adolf Hitler rose in power, and the Jewish population of Europe was perishing at a rapid rate as a result of his leadership. The “ideal” human beings, in Hitler’s mind, were “Anglo” men and women with blue eyes and gold hair. Therefore, many people who did not fit that description fled their countries to seek refuge in places like America. The English phrase “the melting pot” was coined as a result of the mixing of peoples. Valdez, director of the film “La Bamba” once referred to the word as a horrible term, stating that “You melt people down, God! It shouldn’t be that way. Our country should be a place where the individual is sacred” (Gomez, 106). Jose Vasconcelos’ referred to an ideal, future “mixed race” as “The Cosmic Race”.

Not long after World War II concluded, another war began; the so-called “Cold War”. The rumbling of the Cold War infiltrated conversation in the corridors and barrios of the United States as early as 1947. The Cold War would go on until 1991. It was also at this time that the communist ideology was rising in Europe and Asia. The very fear of communism seeping its way into everyday American life consumed the minds of the masses in the United States. Personal and professional lives became frozen, for the time being, so that measures could be taken to ensure the safety of the people; bomb shelters were being built, tested, and advertised through television sets of American families (Shaw, xv). Growing concern about the possibility of another atomic catastrophe was a candle kept lit behind everyone’s eyes at all times during this period. These details explain how Ritchie Valens’ mother, Concepcion, ended up working at a factory that mass-produced products of war. “The importation of Mexican labor power accelerated during war time, primarily through a combined process of…contract labor migration and the internal movement of the resident Chicano population” (West/Macklin, 43).

The idea of increased jobs may sound promising, but that is not always the case. Many of these factories were being built solely to manufacture and distribute weapons used for killing in potential future wars, and these jobs were given to members of working-class and migrating families. The problem with this was the approach that American manufacturers took in making profit. The marginalization and exploitation of Mexican immigrants, especially, was at one of its worst peaks during war-time. American industries went into Mexico and recruited workers during what they called a “domestic labor shortage” in the United States. The average income of these Mexican families was $790 a year, which was $520 less than the government recommended for feeding and housing a family in the Southwest (Gomez, 62).

The migration and influx of Mexican immigrants to places like Los Angeles affected the lives of the Mexican-Americans who had already been living in the area, those who were on the verge of economic assimilation. Progress was being wiped out for the Mexican-Americans or Chicano communities, and, by now, both Mexicans and Mexican-Americans were being paid poor wages, given less benefits, and were being forced to work longer hours. The unjust behavior of production companies is only one example of how the Mexican and Chicano population were treated in the United States during the booming 1950s. This unfair treatment led to the increased establishment of Chicano gatherings where issues were discussed, and it is these moments that led to a wave of Chicano socio-political movements in the 1960s, where farm worker and civil rights leader Cesar Chavez would lead the Chicano community into workers’ reform. While some Chicanos were planting the seeds of social reform, others were planting seeds in other areas of Chicano livelihood. These were seeds that would, by the late 1950s, become Ritchie Valens, and other Chicano figures that transformed the image of Chicanos and Mexicans in American society.